Limitations

Over the course of the project, it became apparent that our data sources presented real challenges to a computational approach to understanding the motivations of funding mission schools to Native Americans. Where possible, attempts were made to address these limitations through supplemental data collection. On this point, two items must be noted.

Missing Federal Reports

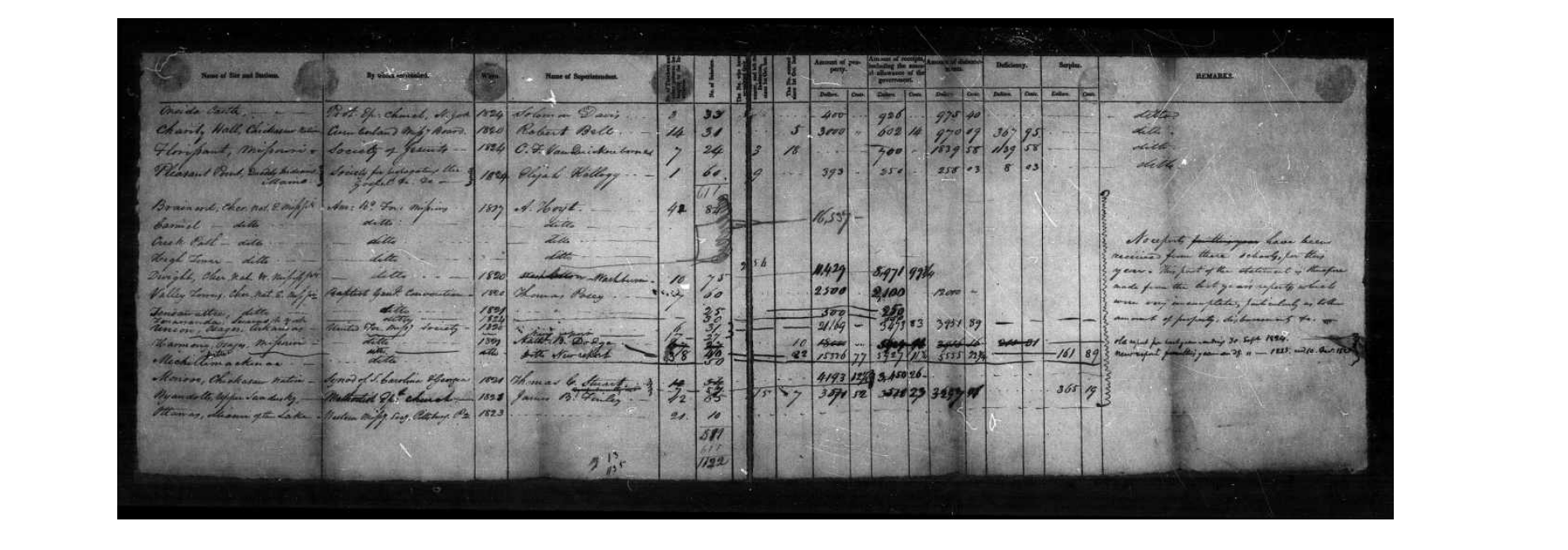

In the process of collecting data from both missionary and federal sources, it quickly became evident that federal reporting was inconsistent on a year-to-year basis for many groups. For example, Figure J shows a highpoint in federal reporting in 1825 with a gradual reduction in reporting for subsequent years. While there is documentary evidence to suggest that there was a general reduction in the number of mission schools, it is no where near the number reflected in the available reports.

Simply put, many groups were inconsistent in the sending of federal reports on a yearly basis. Sometimes, this inconsistency was even noted in reports from subsequent years. This gap could have several explanations. Reports may have been lost in transit, submitted improperly, or simply not submitted in the first place.

While the latter might seem an odd suggestion considering the Civilization Fund’s free provision of resources, it may not be as strange as one might expect. As our data demonstrated, federal funding contributed a meager portion to missionary organizations’ budgets. What is more, funding tended to arrive with our without the annual report submitted from the year before. The incentives for reporting, then, were relatively low.

Note on the Use of Data

Considering the above inconsistency, important caveats must be included about the correct usage of this data. First, and foremost, it should be clear that raw totals derived from federal reporting data cannot all be given equal weighting. For example, one can compare the different ways information can be derived on indigenous student enrolled in the school. Figure K gives a total of all indigenous students (grouped by tribe) according to federal reports. Figure B shows the ratio of indigenous students to federal reports received.

While Figure K suggests there is an apex of student enrollment in 1825, the data is actually reflecting the apex of reporting. Figure B suggests that (except for 1820) student enrollments remained steady throughout the period. This reporting bias was considered in this study. Should future researchers utilize this data, this bias should likewise be accounted for.

At the same time, this reporting bias does not so corrupt the data that a generalizable picture is impossible 1825 was a highpoint for reporting, as well as funding. When analysis is pointed towards the dynamics of federal funding, this data bias may become an asset.